1 Introduction to Warehousing

Have them gather all the food produced in the good years that are just ahead and bring it to Pharaoh’s storehouses. Store it away, and guard it so there will be food in the cities.—Genesis 41:35-36

1.1 🧠 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand the timeline of warehousing operations.

- Discuss the rationale for holding stock.

- Discuss the added value of warehouses in the supply chain.

1.2 What is a Warehouse?

Start with the simplest picture. A warehouse is a place that holds goods. Traditional dictionary definitions reflect this basic role:

A building where large quantities of goods are stored, especially before they are sent to stores to be sold. — Oxford Dictionary

A structure or room for the storage of merchandise or commodities. — Merriam-Webster Dictionary

These capture storage, but they miss what modern warehouses actually do. Because of e-commerce and new service expectations, many sites are centers for storage and centers for value addition:

Today, warehouses operate not only as centers for storage but also as centers for value addition. Several warehouses have assembly, packaging, and repair operations within their premises. (De Koster and Delfmann 2017)

1.3 Warehousing Through the Years

Modern warehouses blend manufacturing tasks, transportation coordination, and storage activities.

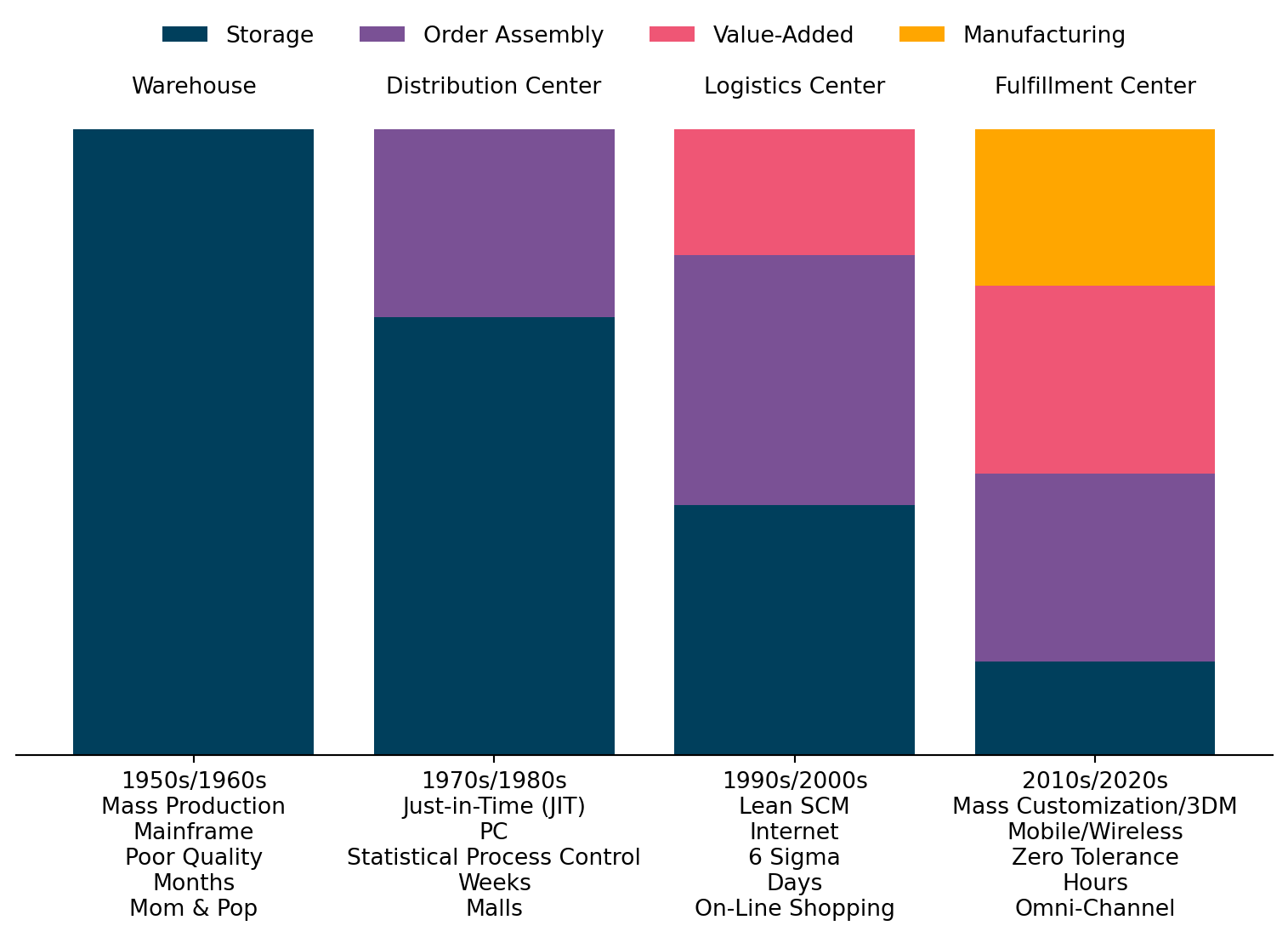

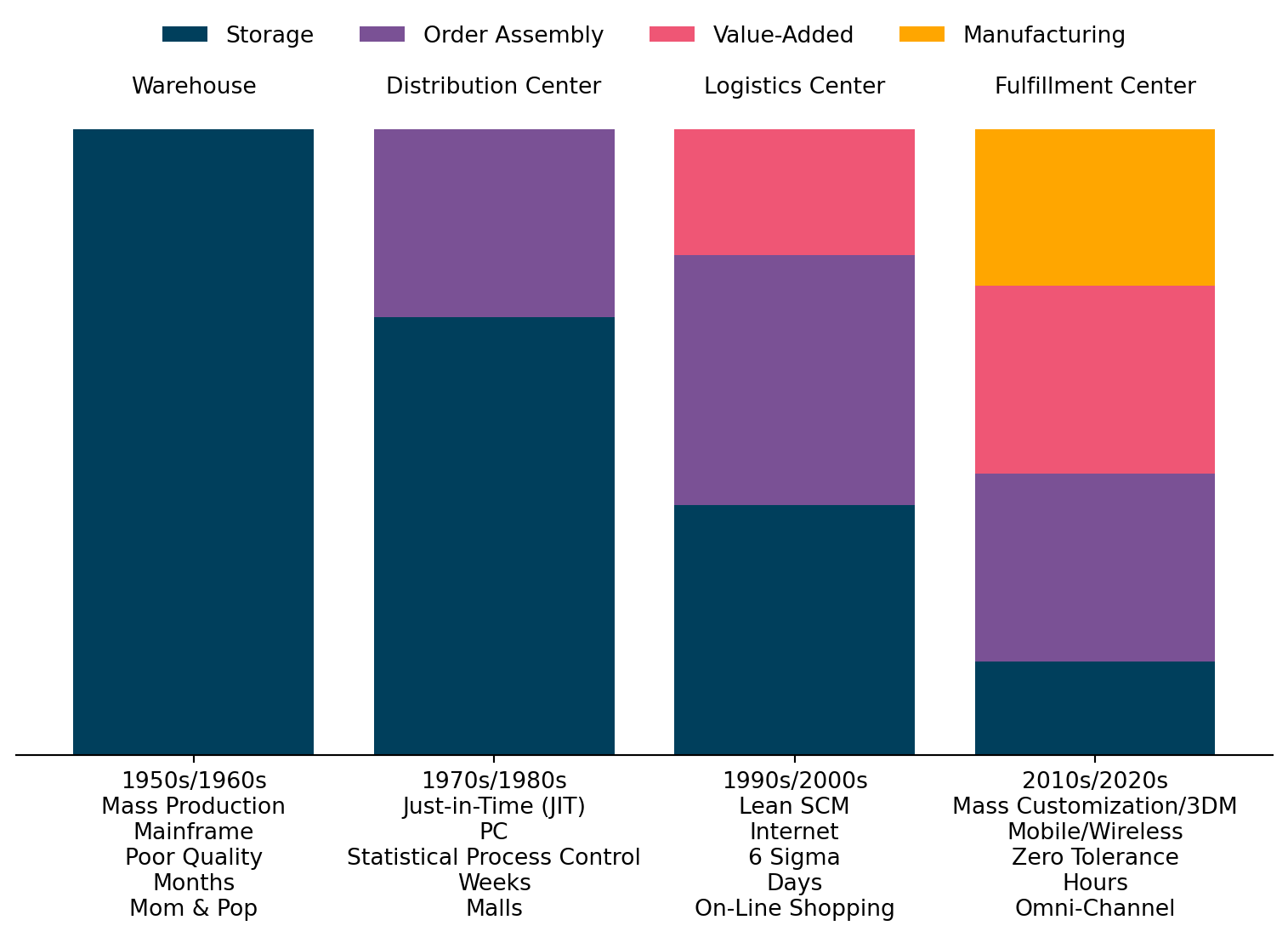

Frazelle (2016) highlights a shift from traditional warehousing to more dynamic fulfillment centers that prioritize speed and flexibility. In the 1950s and 1960s, facilities were almost exclusively dedicated to storage. As supply chains advanced, storage gradually decreased while additional functions emerged. By the 1970s and 1980s, order assembly became an important complement to storage. In the 1990s and 2000s, logistics centers introduced value-added services alongside order assembly. Finally, in the 2010s and 2020s, fulfillment centers focused increasingly on value-added activities and even manufacturing assembly, leaving storage as a minor component. This shift highlights the transition from static warehouses to dynamic fulfillment nodes within modern supply chains. Figure 1.2 illustrates the historical evolution of warehousing and fulfillment functions over the past decades:

- 1950s–1960s. Storage dominates. Long lead times and infrequent orders make inventory the main task.

- 1970s–1980s. JIT cuts average inventory and increases order frequency. More work shifts to order assembly.

- 1990s–2000s. Postponement and global logistics add value-added tasks, for example kitting and compliance labeling, while storage remains relevant.

- 2010s–2020s. E-commerce and omni-channel pull in light manufacturing and final configuration, with tighter service windows and near-zero tolerance for errors.

1.3.1 External Change Drivers

For decades warehousing was treated as a back office necessity, with little perceived added value. As lean and just-in-time spread in factories, attention to waste naturally focused on inventories in tall racks. Two rapid, deep shifts changed this view: the emergence of global supply chains and the rise of online shopping. Both increased the strategic importance of where and how goods are stored, processed, and shipped.

The Emergence of Global Supply Chains

Competition moved from regional to global, both for customers and for low cost inputs. If we view the supply chain as a network, transportation modes form the arcs and facilities form the nodes. Typical nodes include:

- Manufacturing facilities.

- Warehouses and distribution centers.

- Container terminals (seaports).

- Consolidation and deconsolidation centers.

- Rail yards.

- Cross docks.

- Cargo airports.

Warehousing is not only a pause point, it is also a critical source of inventory visibility and accuracy that enable responsiveness, agility, and cost control in global operations.

Growth of Online Shopping

E-tailing, or electronic retailing, experienced rapid growth globally as consumers increasingly turned to online platforms for their shopping needs. This shift was driven by advancements in technology, widespread internet access, and changing consumer preferences for convenience and variety. Online retail sales surged across regions, with significant growth observed in markets like the United States, Europe, and Asia. Warehouses played a pivotal role in supporting this growth, evolving from simple storage facilities to dynamic fulfillment centers. They became critical in ensuring accurate order picking, efficient packing, and timely shipping, transforming warehousing operations into a key component of the e-commerce value chain.

Warehousing Today

Under e-commerce, supply chain collaboration, globalization, quick response, and just-in-time, warehouses face more demand with tighter constraints:

- Expectations. Execute more, smaller transactions; handle and store more distinct items; provide more customization and value added services; process more returns; receive and ship more international orders.

- Constraints. Less time to process each order; less margin for error; fewer skilled workers; limited warehouse management system capability due to legacy enterprise investments.

This challenging reality underscores the importance of mastering fundamentals and adhering to best practices.

1.4 Why have Warehouses?

A practical way to see warehousing value is to walk through five components of supply chain strategy:

- Customer service.

- Inventory management.

- Supply (sourcing).

- Transportation.

- Warehousing.

Warehouses should be decided last. Good choices in the first four may eliminate or minimize the need for storage and processing. In poorly coordinated chains, warehouses often become the physical manifestation of missing integration and planning. In well designed chains, warehouses still provide indispensable buffering and value added services, especially as global chains lengthen and disruptions become more frequent.

1.4.1 The Rationale for Holding Stock

We hold stock at different scales in our daily life. For example, we keep a few days of groceries at home, a few clothes in our closet, and a few weeks of supplies at work. Businesses hold stock for similar reasons, but on a larger scale. Inventories are held to buffer against variability in supply and demand, to achieve economies of scale in production and transportation, and to hedge against uncertainty and risk.

One of the major challenges in managing a supply chain is that demand can change quickly, but supply takes longer to change (Bartholdi and Hackman 2019).

Warehouses are expensive in labor, land, equipment, and information systems, yet perfectly coordinated systems that eliminate warehousing do not exist in real global networks. Goods must be stored either at production, at consumption, or at intermediate points. The task is to size and position inventory so that service is maintained at least cost.

Why not rely solely on zero stock philosophies such as just-in-time or lean production? These systems can be fragile when confronted with long global lead times, port congestion, pandemics, weather, or geopolitical events. A resilient network often requires stockpiles in strategic locations to absorb shocks and maintain service when supply collapses or demand surges.

flowchart LR

subgraph "Plant Warehouses"

RM["Raw<br>Material<br>Warehouse"] --> WIP["Work-in-Process (WIP)<br>Warehouse"]

WIP <--> PW["Plant<br>Warehouse"]

RM --> PW

end

subgraph "Finished Goods Warehouses"

PW --> FG["Finished<br>Goods (FG)<br>Warehouse"]

FG <--> OW["Overflow<br>Warehouse"]

end

subgraph "Distribution Centres"

FG ---> HD["Home<br>Delivery DC"]

FG ---> OC["Omni-Channel<br>DC"]

FG ---> RD["Retail<br>DC"]

FG ---> CD["Cross-Dock<br>DC"]

end

subgraph "Final Destinations"

HD --> H1(("Home 1"))

HD --> H2(("Home 2"))

OC --> OH(("Home 3"))

OC --> OS(("Store 1"))

RD --> RS1(("Store 2"))

RD --> RS2(("Store 3"))

CD --> CD1(("Store 4"))

CD --> CD2(("Store 5"))

end

%% Styling

classDef plant fill:#a8dadc,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px

class RM,WIP,PW plant

classDef finished fill:#457b9d,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

class FG,OW finished

classDef dc fill:#ffb4a2,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px

class HD,OC,RD,CD dc

classDef home fill:#bde0fe,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px,shape:circle

class H1,H2,OH home

classDef store fill:#caffbf,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px,shape:circle

class OS,RS1,RS2,CD1,CD2 store

1.5 How Does Warehousing Support Supply Chains?

1.5.1 Warehousing and Customer Service

Warehousing directly supports customer service by:

- Making inventory available where and when needed.

- Shortening response times.

- Enabling customization (postponement).

- Consolidating items from multiple sources.

- Handling returns efficiently.

These services improve perceived quality and can increase sales.

High Inventory Availability

To achieve high customer fill rates1, firms typically need safety stock2. That stock must be housed, usually near demand. Correctly sized safety stock increases the likelihood of complete orders on the first shipment.

Shorter Response Times

Response times fall when warehouse order cycle time3 is short and when facilities are closer to customers. Examples include networks of small sites with same day service and increased warehouse count and capacity to boost delivery frequency and freshness for large store networks.

Customization

Postponement4 defers product differentiation until the last responsible moment. Warehouses are natural sites for value added services, such as:

- Labeling, special packaging, pricing, and countrifying.

- Assembling and kitting.

- Monogramming and coloring.

By storing generic inventory and customizing near the customer, firms can reduce total stock and increase responsiveness. Example: shampoo in blank bottles is stored and country specific labels are applied in line with picking once an order is confirmed.

Consolidation

Customers expect related items to arrive together. To avoid split deliveries, products from different suppliers must be brought under one roof and consolidated into single shipments.

Returns

Convenient and inexpensive returns increase sales and satisfaction. Warehouses and distribution centers are usually near customer bases and have the staff and equipment suited to receiving, inspecting, and processing returns.

Physical Market Presence

In some markets, a physical presence signals commitment and credibility. A warehouse communicates that the business is present, reachable, and invested in service.

1.5.2 Warehousing and Inventory Management

Because warehouses house inventory, they support the same business purposes as inventory: production economies of scale, seasonal balancing, and risk mitigation through contingency and disaster stock.

Production Economies of Scale

Setups and changeovers will never disappear completely. When setup cost or time is significant, longer production runs reduce average cost. The resulting lot size inventory5 must be stored, typically in warehouses.

- Example: in a food and beverage case, production lot sizes had been set about 50 percent below the economical level, increasing changeover and production costs. Adding about 150,000 square feet of storage unlocked the savings.

Demand Seasonality

Some products have strong seasonal peaks.

- If capacity is sized for the peak, it may be underutilized most of the year.

- If production is leveled, seasonal inventory is built and stored.

Examples: Card manufacturers build ahead of Christmas and Valentines, and frozen pie production for holidays is smoothed and stored in third party cold warehouses.

Contingency and Disaster Inventory

Beyond standard safety stock, firms may hold additional inventory for low probability, high impact events:

- Hurricanes, floods, snowstorms.

- Labor strikes.

- Unusual supply chain disruptions.

Telecommunications and utilities often plan explicit contingency inventories to maintain service during such events.

1.5.3 Warehousing and Sourcing

Warehouses can reduce landed cost by allowing opportunistic purchase and storage of inputs, accommodating economical lot sizes, and hosting on site vendor managed inventories that postpone title transfer.

Production and Materials Cost

If raw material cost dominates the product, then buying at favorable prices and storing the input can lower total landed cost. Some commodity intensive manufacturers forecast input prices (for example sugar or cocoa), time purchases, and house those inputs until needed. Long production runs also lower unit production costs when margins are high, carrying rates are low, obsolescence risk is low, and shelf life is long. Warehouses store the resulting batches until they flow downstream.

Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI) Warehouse

In VMI, an upstream supplier replenishes a downstream partner based on visibility of inventory levels, actual demand, and forecasts. The supplier decides quantity and timing, which often improves transport utilization and lowers downstream stock.

Information sharing. Upper echelon partners share inventory levels, actual demand, and forecasts. The supplier uses this to plan replenishment (Çetinkaya and Lee 2000). For example:

- Nijhof Wassink provides an online portal where suppliers monitor customers’ actual stock levels per company, silo, and product type, so production can match consumption (link).

- Heineken achieved about 7 percent higher transport utilization while reducing stock at a customer DC by roughly 70 percent under VMI (Van der Plas-Rolf, De Kok, and Fransoo 2019).

1.5.4 Warehousing and Transportation

As firms ship more frequently in smaller quantities to reduce inventory, warehouses restore transportation economies of scale by consolidating shipments and can also delay duty payments through bonded storage.

Consolidation for scale. Warehouses accumulate and assemble small shipments into larger ones:

- LTL into FTL. Less than truckload (LTL) shipments are consolidated into full truckload (FTL) shipments.

- LCL into FCL. Less than container load (LCL) shipments are consolidated into full container load (FCL) shipments.

- Transloading. Transloading from 40 foot to 53 foot containers for inland moves.

Figure 1.4 shows an example of how a consolidation center operates. It may receive shipments from various origins (suppliers, parcel carriers, and regional distribution centers) and consolidate them for more efficient transportation to the next nodes in the supply chain.

flowchart LR

%% Subgraph for Origin

subgraph ORIGIN["<b>Origin</b>"]

S["Suppliers"]

P["Parcel<br>Carriers"]

R["Regional<br>DC"]

end

%% Subgraph for Consolidation

C["Consolidation<br>Center<br/>"]

%% Subgraph for Destination

subgraph DEST["<b>Destination<b>"]

E["Customers"]

F["Micro<br>Consolidation<br>Point"]

G["Retailers"]

end

%% Flows

S --> C

S --> P

S --> R

P --> C

R --> C

C --> E

C --> F

C --> G

%% Reverse Logistics

E -.->|"♻ Recycling / Returns"| C

F -.->|"♻ Recycling / Returns"| C

G -.->|"♻ Recycling / Returns"| C

%% Styling

classDef origin fill:#003f5c,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

classDef consolidation fill:#7a5195,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

classDef destination fill:#ef5675,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff

classDef reverse fill:#ffa600,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px,color:#fff,stroke-dasharray: 5 5

class S,P,R origin

class C consolidation

class E,F,G destination

class E,F,G reverse

Bonded warehouses. These allow consignees (i.e., importers who store goods in a bonded warehouse) to postpone customs duties until goods are withdrawn. If located in free trade zones, some in transit goods can pass without duties being assessed. Benefits typically include:

- Minimizing import duties by timing clearance.

- Improving cash position by postponing duty payment.

- Paying no import duties if goods are re-exported.

1.6 Summary: Reasons to Hold Inventory

Holding inventory serves several key purposes in supply chain management.

According to Lambert, Stock, and Ellram (1998):

- Achieve transportation economies.

- Achieve production economies.

- Take advantage of quality purchase discounts and forward buys.

- Support the firm’s customer service policies.

- Meet changing market conditions and uncertainties.

- Overcome the time and space differences between producers and customers.

- Accomplish the least total cost logistics commensurate with a desired level of customer service.

- Support just-in-time programs of suppliers and customers.

- Provide customers with a mix of products on each order instead of single product shipments.

- Provide temporary storage of material to be disposed or recycled.

- Provide a buffer location for transshipment.

According to Richards (2014):

- Handle uncertain and erratic demand patterns.

- Trade off storage, transport, and shipping costs.

- Get discounts via bulk buying.

- Shorten distance between manufacturer and end consumer.

- Cover for production shutdowns.

- Increase economical production runs.

- Manage seasonal production.

- Handle high demand seasonality.

- Store spare parts.

- Store work in process.

- Hold investment stocks (for example fine wine).

- Store documents.

1.7 Conclusion

Warehouses buffer supply chains against variability and delay:

Demand changes (for example Black Friday, new product launches):

- Surging demand implies stockpile inventory to prevent stockouts.6

- Collapsing demand implies slow or hold inventory to avoid forced markdowns.

Supply changes:

- Surging supply implies accumulate inventory if price breaks offset storage cost.

- Collapsing supply implies draw down stockpiles to maintain service.

Other drivers: variable transportation lead time, price increases, high setup costs amortized via batches, and the bullwhip effect that amplifies upstream variability.7

1.8 Question

How can warehouses help mitigate the impact of the following business challenges?

1.8.1 Challenge 1: Lost Or Delayed Overseas Shipment

You run a manufacturing company that imports products from overseas. What would you do if one of your inbound shipments is lost at sea, impounded by customs, captured by pirates, or caught in a port strike?

Hints: contingency inventory at alternate locations, bonded storage to ease reconfiguration, diversified nodes to reduce single point risk. See Section 1.5.2.3 and Section 1.5.4.

1.8.2 Challenge 2: Sudden Demand Spike And Back Orders

You work for a wholesaler with steady sales that suddenly double in a month. There is not enough inventory to fill orders and back orders arise. How can you prevent dissatisfaction?

Hints: safety stock sizing, seasonal balancing, postponement to keep generic stock flexible, network design that shortens response times. See Section 1.5.1.1, Section 1.5.2.2, Section 1.5.1.3, and Section 1.5.1.2.

Cases adapted from Stanton (2022).

1.9 References

Fill rate. Portion of a customer’s demand satisfiable from on hand inventory.↩︎

Safety stock. Extra quantity held to protect against variability in demand and supply.↩︎

Warehouse order cycle time (WOCT). Elapsed time from order release to picked, packed, and ready to ship.↩︎

Postponement. Deferring creation of variants or customization until late in production or distribution.↩︎

Lot size inventory. Quantity produced or ordered per run, chosen to balance holding, setup, and ordering costs.↩︎

Stockpile inventory. Storing large quantities of goods, often to capture purchasing advantages or hedge risk.↩︎

Bullwhip effect. Demand distortion that grows upstream in a supply chain.↩︎